Story of a Game: DOOM

Games have stories. Not just stories of how they were developed—but stories from the people who played them and how they affected the gaming world.

In this series, Ultimate Gaming Paradise will bring you some of those stories. From headline-making triple-A titles to some indie masterpieces.

For our first chapter… we start with DOOM.

A short backstory

It’s impossible to discuss the story of DOOM without spending a little bit of time stepping back and looking at its predecessor Wolfenstein 3D. Wolfenstein 3D was a staggering, groundbreaking moment, where the developers who would become id Software (always stylised with the lower case ‘id’ and pronounced as one word) did something that pretty much no one had ever done before: they put the game camera in the eyes of the protagonist.

Games of the time were side on; things like Super Mario Bros., where you bounced from left to right on your horizontal quest, or Xenon II: Megablast, which viewed your spaceship from the top, looking down. Arcades were teeming with Street Fighters or Double Dragons, with third-person views of muscled men who kicked and punched their way to victory, and even the subtle delight of Elite years before (which arguably did have a first-person 3D viewpoint) was a thin wireframe image of simple shapes. Wolfenstein 3D gave players three-dimensions with depth, bright colours and shapes, and smooth movement that allowed you to spin, strafe, and step in a seamless motion.

It was a defining moment in computer game history, but, to all intents-and-purposes was little more than a demo for what was to come.

Improving equipment

“Do you have a DX2-66? I need one.”

DX2-66, a combination of letters and numbers that in 2021 are completely meaningless, but in the early days of DOOM, pretty much defined whether you were a true gamer or just someone messing about on the outskirts.

The 486DX2-66 CPU was Intel’s top-end chip of the time, and if your PC came with one inside, it meant that it had the awesome power needed to deliver the full experience that was DOOM. Wolfenstein had been playable on the ageing 386 machines and seemed like a powerhouse on a 486, but the second generation of 486 chips was needed if you really wanted to see DOOM fly.

Such was the impact of DOOM in those early days that little independent computer shops up and down the country were fielding queues of avid enthusiasts looking to upgrade to the latest hardware—for no other reason than DOOM.

A game that sold hardware? Typically that sort of impact was reserved for exclusive titles like Sonic on the Megadrive or Mario on the SNES. For something to be shifting the PC market like that, it had to be special.

And it was.

Turning the DOS-PC into a gaming machine

The early 1990s were a time of computing revolution. For schoolchildren across the UK, computers were finally becoming part of their regular learning. Schools were fitted with IT rooms, with as many as sixteen computers on rows of desks. Parents were coming home from the office discussing the newest tools to help them with their work, whether it was accounting software or the latest in computer-aided design.

And the system that was dominating at the time? Microsoft. Whether it was through older text-based MS-DOS, or Windows 3.1, the software company was weaved into companies’ infrastructures all over the world.

However, the thing about a Microsoft-based PC of the time was that it was really, really bad at playing games—at least, anything that wasn’t turn-based. If you liked gaming, you turned to Nintendo or Sega or (for console-haters) the Amiga. You didn’t get a PC.

Until DOOM.

DOOM ran on MS-DOS architecture. This meant a couple of things: first, it turned every household PC into a true gaming powerhouse (assuming it had that DX2 processor), and it also turned every school IT room and office network into something completely new: a Deathmatch arena.

The development of DOOM

DOOM didn’t come from nowhere. John Romero and John Carmack were two enthusiastic programmers, the type of people that didn’t stay at work late because they were asked to, but because they couldn’t believe that anyone would actually pay them to make games. And they were always looking to push the hardware. Determined to make games for IBM-PC machines running MS-DOS, they first worked on cloning Super Mario Bros., trying to get that side-scrolling that the NES had perfected onto a computer better known for spreadsheets. It’s a testament to Carmack’s skill that he managed to do it – at 70fps no less, which is a speed still impressive today; at the time, it was unheard of. Were they satisfied with that? Did they lean back and say, “Let’s churn out PC platformers?” No, of course not.

Instead, they formed their own little studio, id Software, and developed the world’s first real-time 3D first-person engine using that same smooth scrolling code that had cloned Mario. The first game to use the engine was, of course, Wolfenstein 3D.

Despite the Nazi-themed game’s success. John Romero wasn’t satisfied. He wanted horror. He wanted dark. He wanted to immerse players so deeply that they would eat, breath and sleep his game (often with nightmares). He wanted DOOM.

id Software were a ballsy bunch, writing cutting-edge code that had attitude and willing to ignore the rules of business that swirled around them. One of their riskiest decisions was to put out a press release for DOOM, promising a number of technical achievements that they hadn’t even developed yet—or even knew were possible. The biggest of these was to offer multiplayer play when the internet and networking were still in their infancy, and nothing like that had been done before.

If they had failed to live up to these expectations, DOOM might have died before it was even given a chance, but by making promises they had to keep, id Software pushed themselves to the line and made it happen. Sure, it was a couple of months late, but December 10th 1993, came with great fanfare.

Marketing with shareware

For id Software and DOOM, shareware provided an avenue for fame and fortune that others never quite capitalised on. But what exactly was shareware, and what did that mean?

Back in the early 90s, the internet was a rarity for many people, confined mainly to universities and big business. For those who did have some sort of connection, it meant long delays as dial-up did its thing and modems bleeped—it certainly wasn’t an efficient way to share software with the masses, not quite yet.

So, the software was more often shared by putting it on physical disks and distributing these in some way—by magazine covers or subscriptions. Those who got their hands on the shareware were encouraged to copy it and let their friends have it too, thus increasing the spread.

For the people at id Software, shareware was a comfortable thing; it had been their model for their early programming work and the method by which Wolfenstein 3D had found its way into so many homes.

But shareware was not something publishers particularly liked. After all, it was essentially giving away product for free. How did that make money?

John Romero wanted to get DOOM out there and saw shareware as the key. His idea was to split DOOM in three, each a separate chapter in the game, and pass the first part out as shareware, encouraging fans to buy parts two and three.

This they did, and the id Software model proved to be a success.

First, via the internet, where initial demand crashed the server repeatedly and then finding its way onto little 3.5” disks to be passed from grubby hand to grubby hand, DOOM spread worldwide.

The other side of the shareware model

DOOM was free!

Not only that, DOOM was designed to be distributed.

The core demographic for playing this new game was made up of teenagers and students, people who typically had fewer spare pennies to spend on games, and those who were also frequenting the computer rooms of schools and colleges. Once one of them got their hands on DOOM, it was mere hours before they all had it, and the previously sedate workspaces were turned into places of utter carnage.

DOOM Deathmatches ruled the screens of PCs everywhere, and no one had spent anything. They would, of course, because they wanted more, but importantly—they didn’t have to.

Friendly software, sent to them by coders who care, programmers that are just like they are, gamers that want them to game; that was the feeling around DOOM, and it was another of the many factors that made the revolutionary game such a success.

The dawn of first-person shooters

Walk into any game shop, browse through any console game library, sift through any site’s reviews section, and first-person shooters are everywhere. So much so that plenty of people see them as the only true form of computer gaming.

DOOM was first.

Even if you argue that Wolfenstein 3D pipped it to the post and was the first FPS game, it didn’t have the component that makes first-person shooters the dominant force they are today; that of multiplayer play.

DOOM was first.

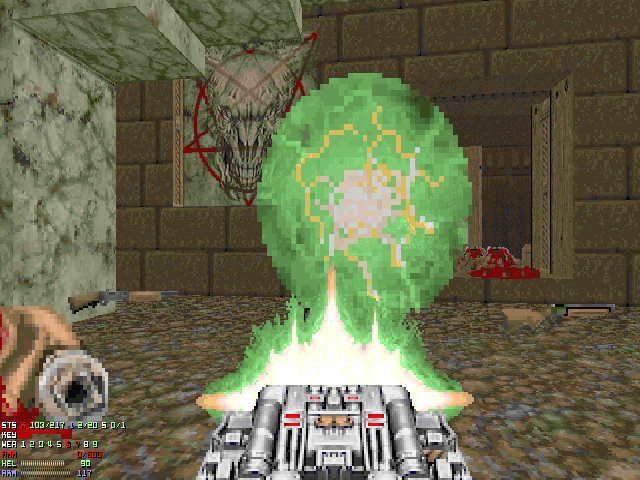

It was with DOOM that you first got that feeling of being in the game, being able to look up into the corner, or the fear of walking into the dark unsure of what will come out. It was with DOOM that you turned the lights off in the room, turned up the little computer speakers that took up desk space on either side of your monitor, and hovered your fingers over W, A, S and D. It was with DOOM that you lost hours fighting demons when you had no friends around, and fighting your friends when you did.

Every other game which puts a gun in the hands of the player and offers you the opportunity to point and shoot something owes everything it has to DOOM.

That’s not a small legacy.

And it’s bigger even than that.

Where’s all the data? Modding DOOM

DOOM was never meant to be a closed environment. Born from a love of shareware, distributed by both long-distance telephone connections and schoolboy swaps, the next deft touch by Romero and friends was to open DOOM up to bespoke alterations: modding.

Modding DOOM could only be done if you had the paid-for version of the game—another clever tick in making it make the developers money, and modding DOOM was a cult all in itself.

id Software handed out documented development tools and adjustable WAD files, which could be tweaked to change any aspect of the game. Want to change the graphics, so the bad guys look like llamas? Go ahead. Interested in swapping the rocket launcher for an ice cream cone shooter? Do it. Have the time to redevelop and re-skin the entire game to look like the Simpsons? Whatever you’re into.

By allowing the players to personalise DOOM as much as they wanted, id Software gave the game longevity that defies belief. Even now, 27 years later, modding communities still enjoy working on their DOOM projects.

Those first memories

DOOM sticks in the mind of those who came across it, creating formative memories for those who were young enough to see it but not necessarily to play, as they watched Dads (and often Mums) hammering at the controls to destroy the demons before they were devoured, and forming a strong nostalgic whimsey for those who were actually at the controls. It’s rare to find anyone who was involved in computer gaming at the time who hasn’t played DOOM because it wasn’t just part of the culture of the early-to-mid 1990s. It was a centrepiece.

DOOM was everything id Software set out to make. It was scary, played in the dark with monsters that came at you from all sides; it was irreverent, with weapons that included the BFG (Big something Gun); it was technically mind-blowing, with all its smooth movement and impressive control response; it was group-friendly if deathmatch can ever truly be regarded as friendly, and it was fun.

The other side of the coin – one last DOOM story

I hated DOOM.

Working in computers at the time, I was at the forefront of upgrading people to those 486DX2-66 machines, which I both coveted and wanted to dismiss. I liked console gaming, I liked my old Amiga, I enjoyed my Apple Mac, and I grew weary of constant PC motherboard upgrades.

But more than that, I was awful at DOOM. I lost every deathmatch I ever played, and I could never find the secrets that other people seemed to take for granted. I disliked DOOM so much that when the genre exploded and first-person shooters took over the gaming scene, I dismissed them and refused to play, sticking to the things I knew best.

It was a shame, because I’d loved Wolfenstein 3D, with it’s brighter environment and amusing “Guten Tag”.

It was years later before I found myself alone and in front of DOOM without distraction or need for bias, and then, like everyone else, I became engrossed in the sheer brilliance of this era-shaping game. I still wasn’t terrific, but I no longer blamed DooM for this shortcoming.

Today, my memories of DOOM are fond. I find myself blessed for having been able to witness this piece of history as it went about redefining computer gaming. It is, and always will be, a legendary achievement.