The Complete History of Role-Playing Games (RPGs): Part 5 – Mastering Dungeons

Ever wondered where the idea of character levels or XP came from? Why fantasy is final? What RPGs looked like before graphics, or what the first massively multiplayer games were like to play? Here at Ultimate Gaming Paradise, we’ve got all those answers and much more in our series, delving into the history of role-playing games.

What was going on in the West while the NES games brought Japanese role-playing ideas to the world?

Episode Five: Mastering Dungeons

You sit in a warm inn, the fire in the corner throwing shadows across wooden tabletops stained with spilled ale. In one alcove sits a lone figure, his hood covering his face…

…so begins a hundred thousand mid-1980s role playing adventures.

It’s hardly surprising that when it came to developing the role-playing experience into a computer game, those classic scenarios popped up again and again, but no more so than in The Bard’s Tale.

The Bard’s Tale

Developed in 1985 for the Apple II (still a stalwart machine for RPG enthusiasts) and later ported to pretty much every computer system available, Tales of the Unknown, Episode 1: The Bard’s Tale was the next development in party-oriented dungeon crawl games following in the tradition started by Ultima and Wizardry.

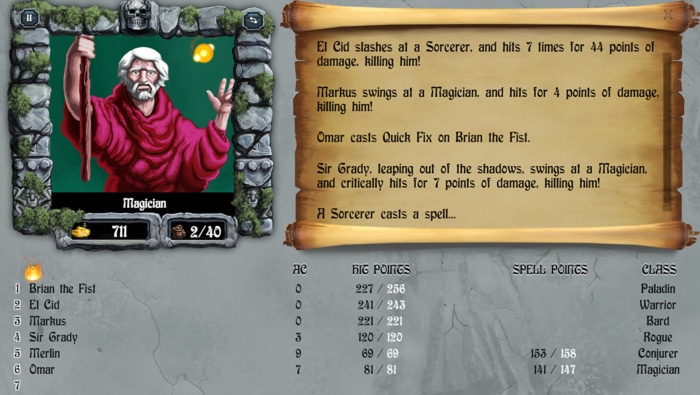

The Bard’s Tale (as it was known, dropping the rather expansive full title), allowed you to develop a group of six characters using a Dungeons and Dragons-like dice rolling system and then take them into various 3D mazes where you would be set upon by random encounters, monsters that you needed to either (F)ight or (R)un from.

You could choose from different classes, each having access to a range of skills, with the mage classes developing later into subclasses (or super-classes, perhaps), giving them an extra level of depth.

Of them all, though, the most interesting was the bard himself, a character that could sing songs to enhance and protect the whole party. It may be true that the bard from The Bard’s Tale is the origin of the very concept of ‘buff’ type spells and effects in today’s RPGs.

But it was the sequel, The Bards Tale II: The Destiny Knight, that really found itself a footing. Winning the Origins Award for Best Fantasy or Science Fiction Computer Game of 1986, The Bards Tale II laid the ground for what was to come, with its wilderness adventuring, multiple towns, and addictive quality.

The Atari ST and Amiga Years

Though the Apple II had dominated the early 1980s in the US for RPG fans and developers, and the NES console was bringing Dragon Warrior and Final Fantasy into homes in the same territory, Europe was somewhat resistant to both. No more so than in the UK—where a staple of BBC Micro, ZX Spectrum, and Commodore 64 home computers had been favoured.

That all changed with the 16-bit generation of game-oriented home computers; the Atari ST and its superior (and somewhat more expensive) competitor, the Commodore Amiga.

The two machines were revolutionary, not just for role-playing games but for games in general, offering superior graphics and multi-channel sound. It was on these platforms that The Bard’s Tale really took off, with Amiga and ST owners swapping pirated copies of the disks compete with photocopied manuals (and thus the meagre copy-protection) in schools across the UK and beyond.

1987/88 marked another landmark period with the release of the seminal game, Dungeon Master.

Pack a torch, you’re going to need it.

Pushing Hardware to Its Limits

Dungeon Master practically defined a subgenre of role-playing games all by itself. While The Bard’s Tale, Ultima and Wizardry had all used the first-person perspective 3D dungeon view in places, with Dungeon Master, developers FTL took it to a whole new level.

No longer stuck in turn-based play modes, this new game took time into account. If you stood still, you could watch as monsters moved through the dungeon. Doors might close before you could get to them, and your light, so important for seeing in a dungeon, would go out, plunging you into darkness.

It was also one of the first games to feature 3D sound, with effect programmed to come from behind if you had the equipment to support it. Spooky stuff; never has a shuffling mushroom engendered so much fear.

Dungeon Master for the Amiga (developed a few months after the Atari ST original) demanded 1MB of internal RAM, an upgrade to the default 512Kb that forced many eager gamers to save up their pocket money for weeks before getting the game. Not only that, but it had copy protection that actually worked, meaning that simply duplicating the disks and passing them to a friend wasn’t enough for them to play. It was immersive and engaging and often played while a group of friends huddled around a TV or monitor in the dark. By far, a monitor was the best experience, as these high-resolution graphics demanded a crisp, clear screen.

With Dungeon Master, players finally felt that they had a computer-based experience that mimicked those great role-playing sessions of dice and miniature figures. Not only that, but it brought many tens of thousands of new players to the genre, coming from general action and puzzle gaming to see what this whole role-play fuss was about.

It had everything; impressive graphics, immersive sound, real-time movement, a clever symbol-based magic spell system, interesting characters, party-centric dynamics, healing, fireballs, and zombies.

Dungeon Master was a true tour de force.

Dungeons and Dragons Officially Enters the Fray

Tactical Studies Rules (TSR) was a company that was well known in the role-playing community. They were the creators of the granddaddy of RPGs—Dungeons and Dragons. To passionate role players of the 1980s, TSR was legendary.

But they were yet to release any sort of computer game.

Why would they? TSR had enough on its hands just covering the behemoth that was AD&D, and getting themselves dirty in this arena of emergent video games based on the system they’d invented was a little too much of a stretch. But, of course, with all that said, they definitely wanted a piece of the pie.

Enter SSI – Strategic Simulation Inc.

An established computer wargame developer, SSI acquired the license for official Dungeons and Dragons computer games from TSR and immediately turned their attention to making games based on the property.

While some early SSI games made little impact on the role-playing world, with side-scrolling action games like Heroes of the Lance long-forgotten despite impressive sales at the time, others did significantly better, helped by the eager interest in the AD&D branding.

One game, Pool of Radiance, kicked off a series of AD&D titles for SSI and gathered impressive reviews and a lot of fans. Pool of Radiance strictly adhered to the AD&D rules, making it a firm hit for those entrenched in the franchise. Still, graphically it felt like a previous generation game and certainly wasn’t up to the standard that was being shown elsewhere.

Simply put, it was no Dungeon Master.

It’s little surprise, then, that what came after was just a little closer to its rival.

In the Eye of the Beholder

”The beholder (eye tyrant, sphere of many eyes) is most frequently found underground, although it infrequently will lair in desolate wilderness.” – AD&D Monster Manual, 2nd Edition.

The Beholder is one of Dungeons and Dragons’ more beloved creatures. A great floating eye with the ability to nullify magic and turn people to stone or laser them to death, it’s an ‘endgame boss’ type monster for the game that has seen many adventurers fall, ending their stories forever.

It made perfect sense that SSI would bring this iconic creature to the fore. After all, if they didn’t, no one else could.

Imitation, they say, is the greatest form of flattery. So, when Eye of the Beholder hit shelves in 1991, the developers at FTL must have felt very flattered indeed.

There’s no doubt in anyone’s mind that Eye of the Beholder is a Dungeon Master clone. It’s so close that you’d swear the code was lifted from one and recompiled for the other, right down to the arrangement of party information, viewing window, and controls.

Eye of the Beholder came out on a great range of platforms. There was an Amiga version, an MS-DOS version, and one for the SNES. There was even an eventual port to the Sega CD (with extra cutscenes) and one for the PC-98.

It was a brilliant game that spawned several sequels, found itself on ‘best games of all time’ lists in the 1990s, and gave TSR and SSI the exposure they needed. In terms of numbers, it actually sold fewer than Pool of Radiance, but the buzz around the game was far greater, and its legacy impact more considerable.

Compared to Dungeon Master, it had a more colourful palette for its graphics, followed AD&D rules for magic and character stats, and was set in the established setting of Waterdeep in AD&D’s Forgotten Realms—all things that gave it a little more oomph in the long term. A game that was well worth playing then, and is still enjoyable today.

The Divergence of Western and Eastern RPGs

All this was going on while Japan was taking a slightly different direction with its Dragon Quests and Final Fantasies. It is interesting to see how the two cultures treated the genre in different ways, and even though in the years that followed, there has been a huge amount of influence from each that can be seen with the other, there’s still a contrast there.

Western RPGs were far more closely tied to the original Dungeons and Dragons model. Here, we would see those classic tropes of a shadowy figure in an inn and a party of young adults ready to do battle. Japan seemed to favour the narrative of the hero’s journey, often starting with a far younger protagonist who is more of school age than likely to have already embarked on a career path.

Perhaps this is to do with their audience. With the NES as the main hardware for JRPGs of the time, the demographic was very much focussed on younger teens, whereas the more-specialised computer systems favoured in the West leaned towards students and young working men.

And yes, it was all very sexist. Hardly anyone developed anything with a female audience in mind. There were token female characters, but never the main protagonist (or party leaders); getting women out of gold bikini armour and into realistic clothing was a change that would be glacially slow in coming (and arguably, we’re still not there).

Eye of the Beholder, Dungeon Master, The Bard’s Tale… For years these games defined the RPGs of the West, with established titles such as Ultima now settled series with their own loyal fans.

By 1990, Ultima had reached Ultima VI, the first of the games to ditch the stalwart Apple II in favour of newer, more advanced platforms. Just as those other RPGs of the age had taken so many hints from earlier Ultima games, now the influences went both ways, with Ultima VI utilising many of the aspects brought to the genre by Dungeon Master. The circle was complete.

It was a fabulous time to be an RPG fan, with a growing selection of top-quality titles emerging, each with enough gameplay value to clock up tens, if not hundreds, of hours.

Coming next…

Remember those early text adventures we looked at in Part 2? Just as the dungeon crawling, action-centric games broke new ground, so too were the story-driven interactive fiction titles. Join us next month where we see what secrets can be discovered on islands by pirates and explore where lewd comedy finds a home.